Bailey Patterson has a background in almost every side of theater. That means she’s seen firsthand how disability is often excluded from those spaces.

“I’ve been witness to a lot of the exclusion of disabled artists and disabled narratives in the greater theater canon,” Patterson said. “Furthermore, when a disability is a subject that I’ve noticed has been included in the theater canon, it is usually being explored as a narrative device, by non-disabled artists, by non-disabled playwrights, non-disabled directors, non-disabled actors, and that leads to a lot of discriminatory stereotypes being brought to the forefront.”

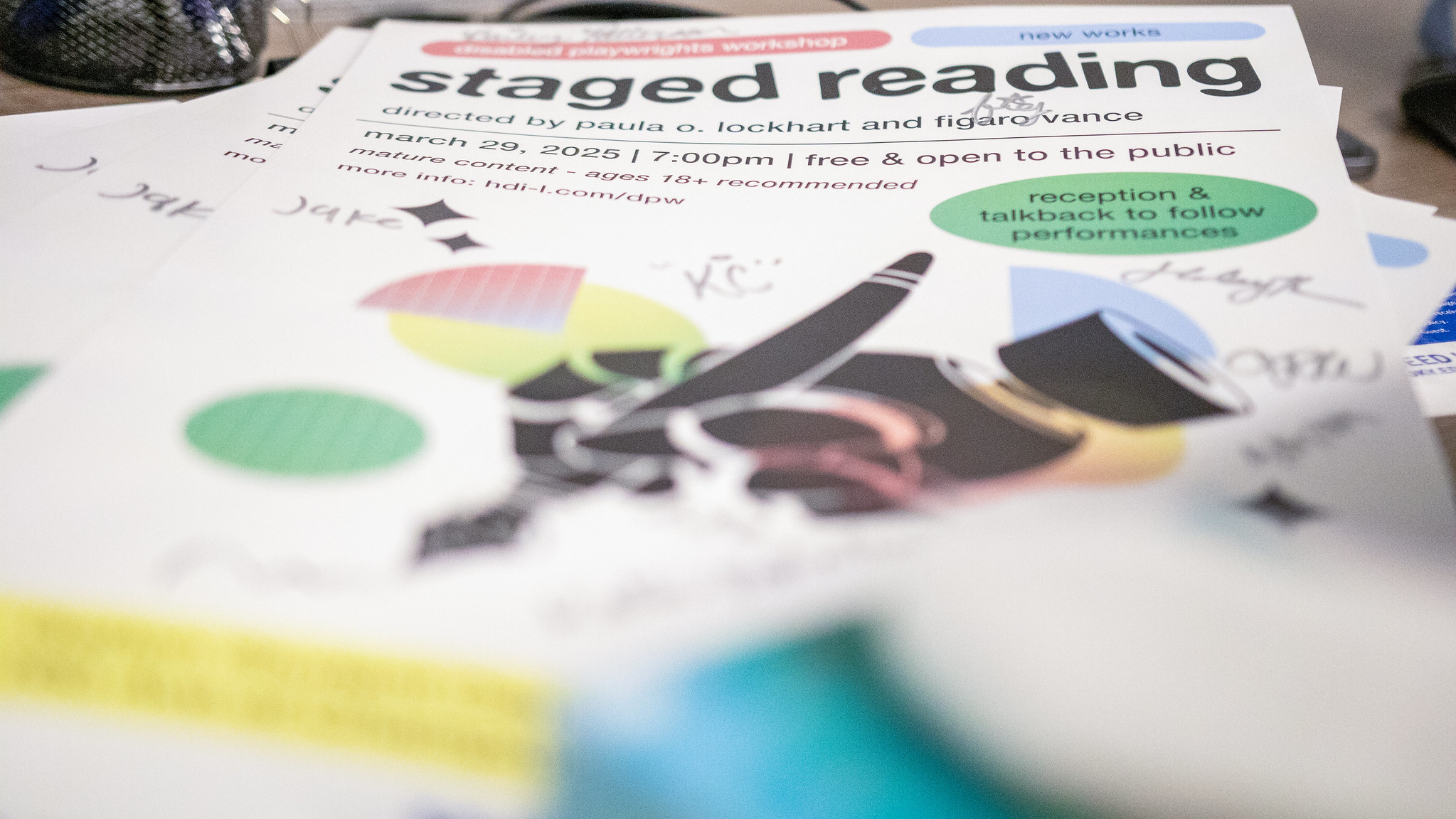

A part of the reason for this, Patterson said, is that people rarely get to tell the stories of their own disabilities onstage. That’s what she and Haley Potter sought to change through the Disabled Playwright’s Workshop. The project, funded through HDI’s Fund For Excellence program, sought to bring these often-ignored voices center stage. The workshop held staged readings of four plays by writers with disabilities, bringing them to life with the help of actors and crew members with disabilities.

Patterson and Potter agreed that new play development was a natural place to start with challenging theatrical culture on the way it sidelines disability. Potter mentioned that she has a lot of experience with new works development in orchestral music and feels that it’s vital for an artistic medium to avoid stagnation.

“Especially in orchestra, everything that we do is dead white men’s work,” Potter said. “That doesn’t keep the art alive…it’s because people keep refusing to work with living composers and librettists and playwrights.”

With a goal in mind, Potter and Patterson put out the call for playwrights to submit works. They did not expect the response they got.

“We had a ton of submissions, and there were definitely several submissions that we really, really enjoyed that ultimately didn’t end up fitting for one reason or another,” Patterson said. “We were surprised to find that almost every submission, and the four submissions that we chose, dealt with disability as a subject. After the fact, two of the playwrights shared with us that they actually wrote the work for our specific call for new works by disabled playwrights.”

In the end, the four submissions that were given full readings were Heard Mentality by Allison Fradkin, Group by Ozzy Wagner, Felt by Katie Peña Van-Zile, and Pillow Talk by JD Otsuka.

Even with a strong quartet of plays to showcase, Potter said the struggles weren’t over yet. Last minute cancellations, venues dropping out, and struggles to find workable spaces haunted the administrative process. Potter said it was a good illustration of how disability is stigmatized in the arts. She mentioned in particular the difficulty in finding a venue, including performance spaces that canceled on their end.

“That’s what stigma is – something that seems as trivial as finding a venue,” she said. “That is one of the reasons why I had so much pushback is because the word ‘disabled’ was in there. And even if they were doing it unconsciously, that is part of the stigma. They didn’t even realize that what they were doing perpetuates exclusion.”

But once the work was done and she got to see the playwrights during a talk-back, Patterson said the emotional impact of the workshop sunk in.

“The idea that people were inspired to write by this opportunity and were able to see their work being staged in front of an audience was extremely gratifying,” she said.